I recently had the privilege of interviewing photographer Jim Herrington. The man has captured the likes of Willie Nelson, The Rolling Stones and Dolly Parton. Music is his first love. But climbing mountains is certainly a close second.

“Somehow I was drawn in through the creaky old back door of all these subjects,” Herrington says. “I started out listening to music that was made before my time, I was exposed to quite a bit of photography from the 30s, 40s, 50s, and the climbing also came to me the same way—from old books, photos, magazines. Something about the past drew me in more than the present.”

Herrington first started climbing in North Carolina, where he grew up. “I wanted to climb long before I actually did it,” he says. “Finally in 1976 when I was 13 years old, I tied in to a rope for the first time and I liked it even more than I imagined I would. I loved climbing from the start.”

When you connect with something so innately, like making music or climbing mountains, you can get pretty creative at making it part of your life’s work. Herrington certainly did that by photographing legendary musicians.

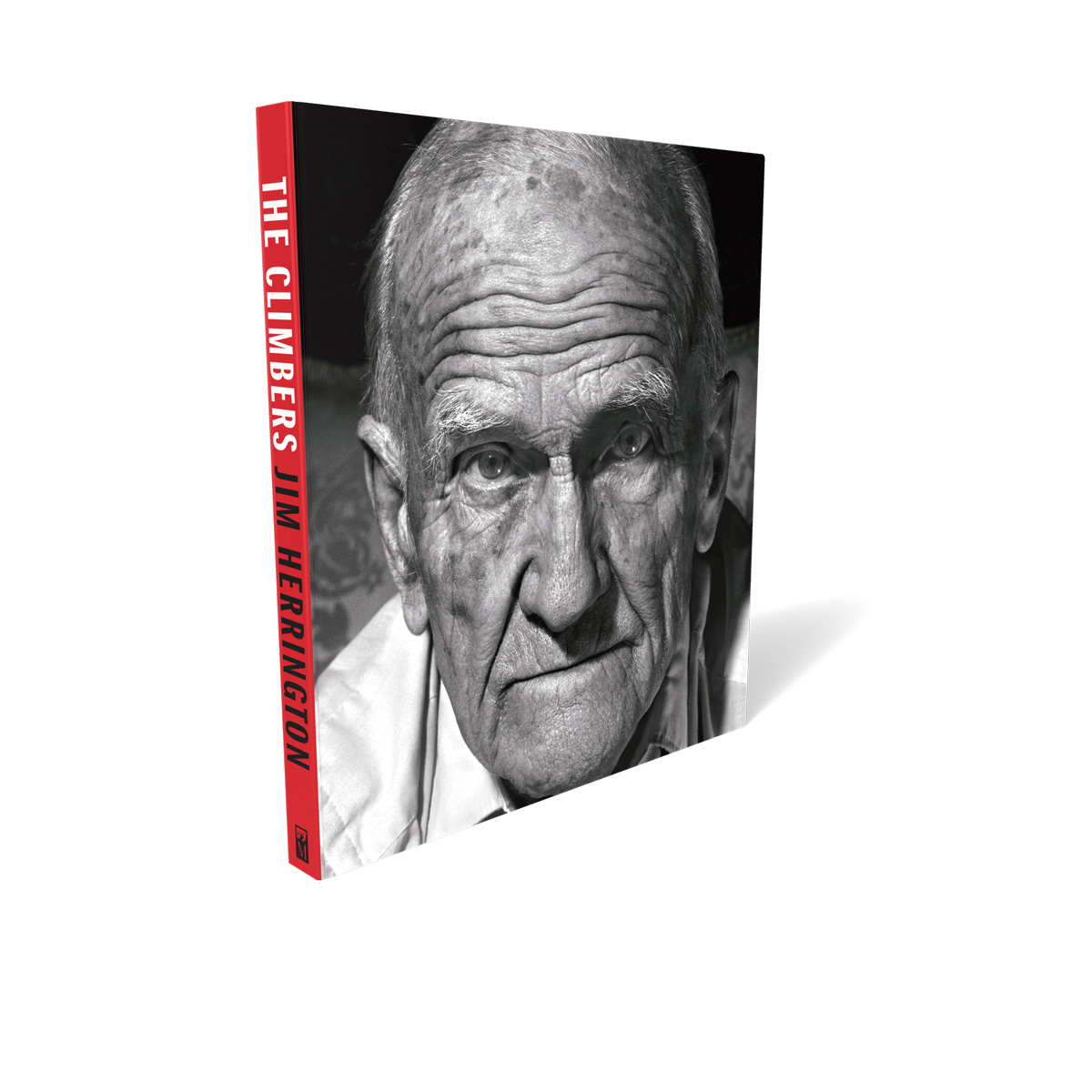

But to research, locate and capture in raw, large-format black-and-whites 60 of the world’s most iconic climbers took him the better part of two decades.

But to research, locate and capture in raw, large-format black-and-whites 60 of the world’s most iconic climbers took him the better part of two decades.

Among the legends from the 1920s to the 1970s Herrington has captured in his book “The Climbers” are:

- Gwen Moffet, who he calls an “early bohemian and a climber through and through,”

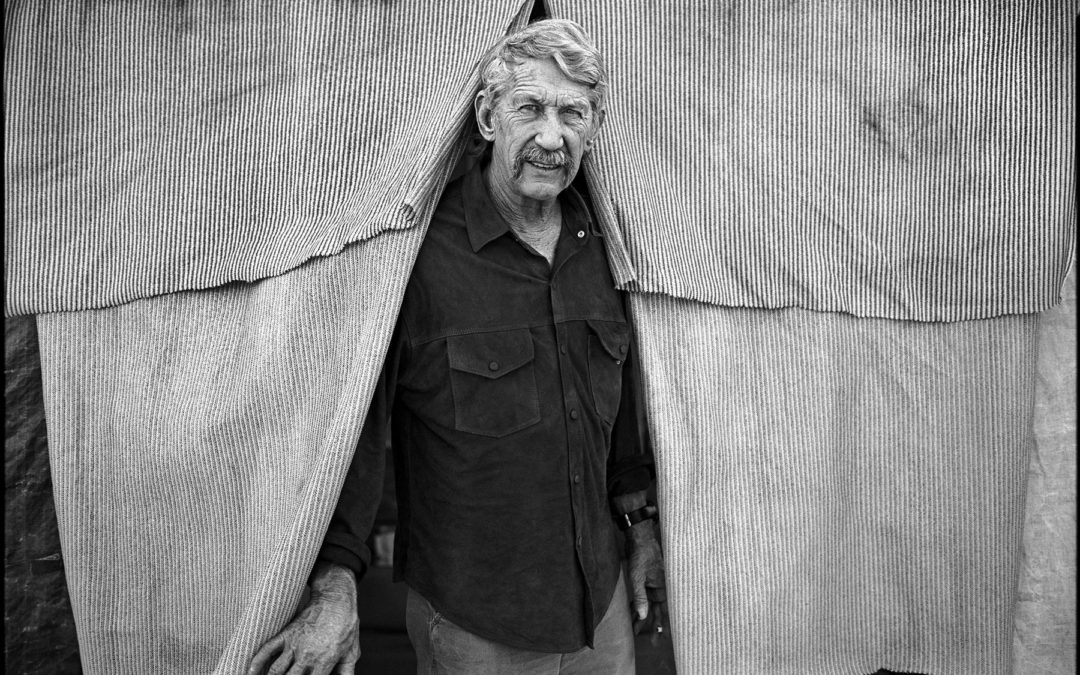

- Jim Bridwell, “climbing’s original pirate,” pictured above,

- Everest sage Pertemba Sherpa, one of the most respected Sherpas of all time,

- Yosemite cragsman Royal Robbins, whose ascents and clean climbing practices were way before their time, and

- Italian climber Riccardo Cassin, who he found holding vigil with family near Lake Como. Cassin died one week after Herrington took his picture.

The magic must have been in the process: The week I talked to him, Herrington’s book took home the Banff Mountain Book Awards’ grand prize.

Thank you, Jim, for reminding me that the creative journey to make something great, something meaningful, is worth the haul—even 20 years and 65,000 miles later.